Many people ask us the difference between gyokuro and sencha green teas...which probably is a subtle way to ask the real question: Why is gyokuro more expensive than sencha?

The practical answer is that gyokuro tea leaves involves much more work to produce. The tea plants for gyokuro are grown in the shade about 20-30 days before harvest. That means the farmer has to put up roofing above the plants. When the shade is put up, the plants are about 70% protected from sunlight. Closer to harvest time, protection rate is moved up to about 90%...which means more roofing adjustments. (Incidentally, tea leaves for matcha are also grown this way.) On the other hand, sencha is grown in full sunlight, all the way to harvest.

How different do they taste?

Very difficult to answer! If you try both teas, you will know the answer...but to put it down in words may be futile! But we shall try!

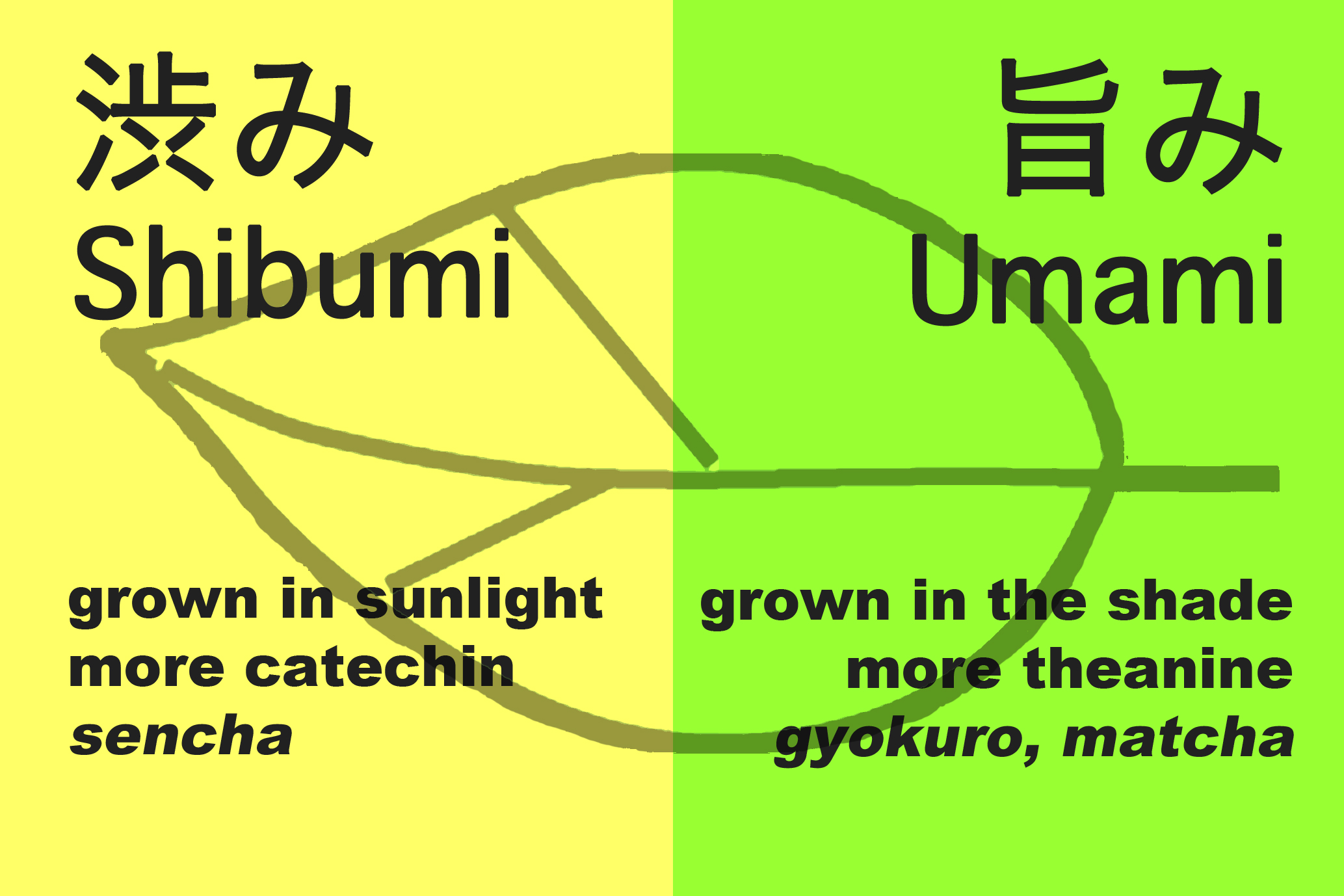

There are two Japanese expressions of taste that we would like to introduce: shibumi and umami. Shibumi is normally defined as "astringency". The Japanese would give the example of the taste of not-sweet persimmon as an example of shibumi. Yet shibumi evidently goes beyond a taste that makes us pucker our lips, especially when it comes to describing the taste of tea or wine. Umami is normally defined as "pleasant savoury taste." Still quite abstract but we may have to venture into poetry to describe it further! :-)

Now back to how the teas are grown... Photosynthesis occurs in the leaves when they are exposed to sunlight. One product of photosynthesis is the bioflavonoid, catechin. More catechin increases shibumi flavour. By suppressing photosynthesis through shading, the farmer produces tea leaves that have less catechin, thus increasing the ratio of the amino acid, theanine to catechin. More theanine increases the umami flavour.

So, is the taste of gyokuro really worth the extra premium?

We will defer to the eloquence of revered Japanese writer, Natsume Soseki (whose image appears on the old 1000-yen note, by the way!) This excerpt is taken from the English translation of his 1906 novel Kusamakura (literally "The Grass Pillow"). The English title is The Three-Cornered World.

For the man of leisure there is no more refined nor delightful pursuit than savouring this thick delicious nectar drop by drop on the tip of the tongue. The average person talks of 'drinking' tea, but this is a mistake. Once you have felt a little of the pure liquid spread slowly over your tongue, there is scarcely any need to swallow it. It is merely a question of letting the fragrance penetrate from your throat right down to your stomach. On no account should it be swilled round the mouth and over the teeth, for this is extremely coarse. 'Gyokuro' tea escapes the insipidness of pure water and yet is not so thick as to require any tiring jaw action. It is a wonderful beverage. Some complain that if they drink tea they cannot sleep, but to them I would say that it is better to go without sleep than without tea.

Natsume, Soseki, The Three-Cornered World (translated from the Japanese Kusa Makura), trans. Alan Turney (1970; reprint, Washington, D.C.: Regnery Gateway Inc., 1988), 113.

No wonder some Japanese tea sets are tiny! :-) It is a matter of savouring rather than drinking. This oribe teacup is just 4 cm tall!

So now, does your gyokuro begin to taste better? :-)

Our recommended steeping instructions for different types of Japanese tea can be found here. At best, they are just suggestions. Taste is a matter of personal preference. After some trial-and-error, we hope you find the formula to best enjoy your Japanese tea!

Further reading: Umami Information by Food: Green Tea

All photos (except where cited) and infographic are by the ikebana shop. All rights reserved.